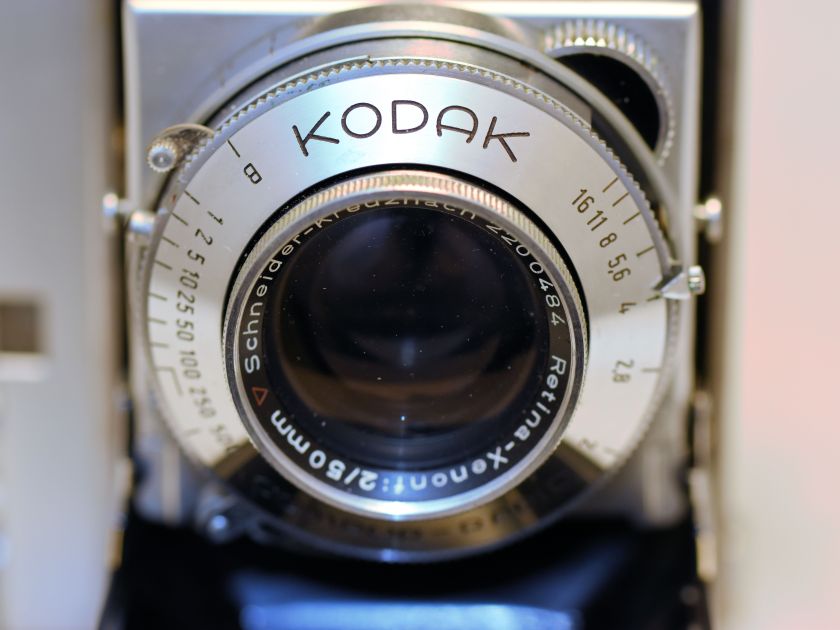

I recently revived my father’s camera, a Kodak Retina II from the 1940’s, as I described in this earlier post. I am fortunate enough to have a local photo shop, called Looking Glass, within biking distance, where I could buy a roll of film. There were very few options, and I was surprised that the Kodak brand still existed. I also saw from the shop’s web site that some films were subject to quotas! I went home with Kodak Ultramax 400 film of 36 exposures. The 400 ASA number felt very high as I remembered using 100 ASA negative films and Kodachrome 64 and 25 for slides. 400 meant I could take photos in lower light conditions, faster speeds, and/or smaller apertures.

It was appropriate that I would use Kodak film in a Kodak camera… I found an image of the original user’s manual (from retinarescue.com) which suggested that of course. The user’s manual shows distance settings in Feet, whereas my father’s model shows them in Meters, a sign to me it had been manufactured in Germany for the European market (and may have included a manual in French). The first photo taken by my father in the archives is dated 1949, which may indicate that’s about the time he bought it (it’s also the late 1940’s period this model was made).

To test and calibrate the light meter, I set my newer Nikon D5500 to 400 ASA and determined it was working, which to me was a surprise because I’m used to having most of everything working on batteries: it turns out photocells don’t need them, and in fact I remember my first SLR, a Konica camera, didn’t have a battery yet had a needle in the viewfinder helping me to set speed and aperture directly.

In fact, this had its own charm in this experiment: there were no batteries to buy and recharge. Everything with the camera was mechanical, and I thought “wow” every time I realized something had been made possible through a mechanism, for example when it could detect I had not wound the film to the next exposure position. Before taking a photo, I had to crank the spring that opened the shutter when I pushed the button. There is a focusing mechanism in the viewfinder that aligns two panes according to how the focusing wheel moved on the lens. After a few tries, I realized the different settings had affected others while I moved them, showing it might need a cleaning and lubrication to avoid them to rub against each other.

And then the camera fell off my shoulder one day, worrying me that it might be the end of the experiment. The leather strap, as I saw it, had already been replaced on the other side of the leather case, whereas the side I had just broken was original.

Recreational photography nowadays gives you instant satisfaction, and here I was taking one photo after another of mostly street scenes around me (I’m lucky to live in Berkeley). Then it rained for a week and I still had half the roll of film to expose… I remember this thing about “finishing a roll” when one needed to go outside and take photos in order to come to the end of the roll and send it for processing.

Another week passed after I dropped it at the shop, and I half expected all blank pictures, or the bottom half of every photo underexposed, etc. But as it turned out, most of the 38 (the first of which was really the half exposed strip) were good! Some were out of focus. Some had exposure issues between a dark subject and a bright sky. Many issues nowadays are resolved by software in the camera (or phone). Yet many prints looked like I could frame them. They had a je ne sais quoi about them, even though at times I saw I aimed the camera a little too much to the right, for example. I have so many photos that reside on my laptop that I may view on a monitor, but I rarely will stop looking at them. Look at the thousands of pictures people have on their phones…

So here it is: the group photo. It’s digital, taken with the Nikon, even with a macro lens, a scene I made from the photo taken of a phone camera taking a picture of a plant, with the actual camera that took it. The phone camera sits on a dictionary which is obsolete because there’s translation software on the phone… The whole picture is about time passing. The Kodak Retina II is about to return to the shelf in my living room, where I will also place its “time passing” framed photo…

I have a photo of my father using his camera (the light meter actually, but the camera and its leather case are visible) in 1980. There may be a few slides he captured in the couple of years that followed, but the camera was never used after he died, in 1983. This project completes the camera’s 75th anniversary. It has been instrumental to my family’s history, maintained our memories as we watched slides on Friday nights in our living room. Here’s to time passing!

I really enjoyed reading this, bibi! What an interesting history that camera had …it has really been around! By the way your Dad looks very handsome and fashionable in that photo! 😎 B xo