That was the title of my Master’s Thesis. It was written in French, at the Université de Montréal. It’s on microfilm at the University’s library (I’m not sure if I kept a copy, in all my moves!). Here’s a paper I wrote in French about it, in which you can see examples of what it did:

My advisor hadn’t been too pushy or specific about what to do, and he was going to spend the year away on sabbatical… I guess that was a good way to let me be creative, even though I didn’t know that word at the time. Self-expression, self-determination, and even self-esteem weren’t part of my upbringing, and I had been told to be quiet early on as a child. But I had chosen this advisor, Paul Bratley, at first because in a presentation of the department’s professors, he had the most interesting field of interest. I shyly knocked on his door, intimidated by his look (what was it? His facial expression said I could be boring), and said I found his idea of setting type in the Inuit language (or whatever he had seen on an airline magazine) interesting.

I’m not sure what ensued, but the next thing I remember was a graduate class project in which I worked with a History grad student to make a map showing all the place names and their relative importance in the writings of Grégoire de Tours, a medieval bishop who had written extensive memoirs. The map was rudimentary for today’s standards, but I learned a lot, even using a large table device to record the contour of a Michelin map of France (and I think subsequently a map of the greater Frankish realm in the times of Charlemagne), figuring out that there once was a Paris meridian, and eventually printing on a thermal transfer printer (this was before laser printers), all through the CDC Cyber mainframe computer that had a 6-bit character set.

I’m not sure if our advisor was in this because he could work with more female students than he could find in CS, but that was an aspect I really wasn’t aware of (apparently I was the only one unaware of the playboy-like pictures in his office). With him I could go to conferences about Computers in the Humanities, which were mysteriously interesting, much more than whatever other students were doing in our department (which I called making systems for systems people). I had a summer job making concordances and other exotic things, like printing a poem in Russian on that thermal printer.

In his laboratory he had a phototypesetting machine, made by Singer (the sewing machine company, which had relabeled the product from a company they’d acquired). It was intimidating, of course. It read paper tapes and used sequences of commands to flash characters on a photographic paper that you’d then feed into a processor. There was a paper tape terminal, and an Interdata computer that was also intimidating. But I learned that I could produce paper tapes from the CDC mainframe, so I could show up at the lab with a tape and ask permission to use just the Singer machine. I’ve always been so timid…

So I was trying to “do something” with this, and as I started looking around at the type used in books, I of course had the example of computer books which set computer programs in elegant type combinations. I wanted to do that. And having worked at making tabular concordances, I also wanted to set those documents because on our mainframe computers the printing was all caps. So I made up my own system to transform text from those sources into typesetting commands.

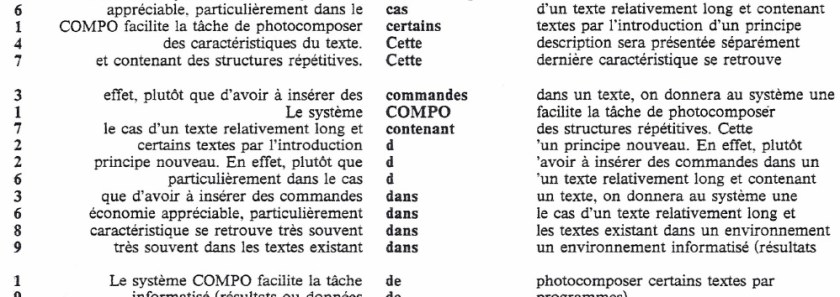

Somehow I borrowed the idea that I could make up a language (from the example of the concordance making software), and my software could interpret that and then process the text accordingly. For example, when I wanted to process the Pascal computer language (the one we used at the time), I would write instructions to turn keywords (like “if” “then” “else”) to bold characters, variable names in italic, but not numbers. It worked! That became my master’s thesis, and I was lucky that my advisor was on sabbatical in Europe, the draft even got lost in the mail, so he actually read it when he came back and had it approved rather swiftly.

Oh the irony, I followed the University’s instructions and typed the thesis on an IBM Selectric (I really liked how they felt), without ever thinking I could have set it in type (that would have been a first, and I never really had the idea you could try to deviate from the norm). The illustrations were, of course, all typeset.

I left the university without asking what else I could do there… Somehow I wanted to find a job, and I was attracted by the idea of going away elsewhere. I interviewed at Control Data in Montreal, but somehow they gave me the impression I was just a body to reshape in their model. I found a job at the Université de Sherbrooke, in the Computer Centre… More on that in a later episode…

Self Critique

It was very much of a programmer’s tool to automatize the heavy editing required to go from a limited character set to complex typesetter commands, so the “text description language” was in fact a small computer programming language itself! Once I had written the description for, say, Pascal programs, I could run it through any number of programs without further intervention. The phototypesetter itself wasn’t very accessible and required a bit of manual attention and intervention (such as making sure it had the right font set). But given it was 1977, it was an early version of what is hidden in word processing software now when it proposes different page formats to apply to your document. One thing that changed was that the character set increased dramatically (in our case from 6-bit to 8-bit and beyond), so the text input is richer (although it’s interesting to notice how almost fifty years later, most information on your travel documents are in capital letters!).

Fun facts

I wrote the software in Pascal. Our version was taught by French people, and the keywords were in French. I learned about compilers in a class, and we had access to the Pascal compiler (written itself in Pascal) on the CDC Cyber. COMPO itself had its own language, and especially in the second version, had a lot of compiler-like features (the second version, written in PL/M on an Intel system generated machine code so it could run in a very small amount of memory).

That knowledge of computer languages somehow was a reflection of my liking foreign languages (at the time, English was my second language, but I had learned some Latin and Spanish in High School). But the analogy is weak because a programming language has a very limited syntax, does not change by differences in speakers, etc.

I still love to type on an IBM Selectric! I also liked using the keypunch (at the time of COMPO, our system offered access through DECWriter terminals, but it was more or less the same batch process and using the Cyber’s 6-bit character set).